A prolific British academic and author, Jeremy Myerson has been a pioneer in the study of design and its impact on work for over four decades. He co-founded the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design at the Royal College of Art (RCA) and was the founding editor of Design Week, one of the world's most prestigious design publications.

Today, he directs WORKTECH Academy, an intelligence network for academics and practitioners to study the future of work and workplace design. In his new book Unworking: The Reinvention of the Working Office, co-authored with Philip Ross, he explores the advent of hybrid workplaces, fuelled by digital technology, design innovation and workforce diversity.

In this exclusive interview with Laba, Professor Myerson shares his thoughts on the future of the office in light of the remote work revolution, the importance of offering a range of choices and “super-experiences” to employees, and the upgraded role of HR departments.

Professor Myerson, is remote work here to stay?

The effects of the pandemic changed how we work, but it was also an acceleration of pre-existing trends. Office occupancy had been falling for decades. It was regularly 60-65%, now it's only going back up to about 50%.

People work more from home and some companies even go fully remote. These are big changes in the corporate mindset. People were already working flexibly before, but it was only tolerated as long as people were not making a fuss about it. Office occupancy was low on Fridays, but senior management just tolerated it.

During the pandemic, all offices were shut down. So firms confronted the fact that people already have the technology to work flexibly. That brought forward corporate acceptance of transformations that people had predicted would last decades. It happened almost overnight.

The picture is mixed on whether we will go back. Managers say that people need to get together for integration, learning, mentoring. Higher-value, interpersonal work is difficult to do online. During the pandemic companies kept the wheels turning, but there wasn’t anything too ambitious. Now leaders want people back in the office to do interpersonal work.

But people had a taste of reduced commuting and more control over their environment at home. They want to have convenience, the option of flexible work. It’s coming out at about 2,5 days in the office.

Offices are still an important part of the ecosystem of work, a digital and physical ecosystem. Not everyone will go back to the office full-time. But offices are part of the future.

Do managers feel that they are losing control?

For all the sophistication of modern business and the finessing of technology, there are deep-grained cultural factors at play, going back to the Taylorist, scientifically managed office where clerks sat in rows and supervisors walked up and down, checking their work. Some of that still exists.

Banks and law firms have been innovative leaders, but are the most vocal in pulling people back to the office. Their argument is that junior lawyers and bankers can only learn from senior partners. That's an old-fashioned way of looking at the world.

Physical proximity plays a role. The Allen Curve shows that the farther away you sit from someone, the less likely you are to communicate with them. So there are advantages in breaking up the week and having days where you sit with your team.

Early in the pandemic, studies of employee sentiment showed a “honeymoon” moment. People stopped commuting, spending more time with their family. They felt happier and more productive. So there was a peak in satisfaction and productivity.

But then it dipped, because people were always online. Microsoft data shows that workers were taking calls later in the evening. They traded commuting time, which is personal time, for more work. People felt burned-out and depressed.

Gensler, an American architectural practice, surveyed 14,000 workers and found that people are coming into the office not just to collaborate, but also to focus. They don’t want to come in every day, maybe two-three days per week. They are looking for a balance.

That's where the workplace will settle: providing a better experience. The so-called “espresso office,” smaller, but more powerful. Firms will rent less space. Leesman, a firm that does utilisation surveys, have said that firms are looking at half the space but twice the experience.

There’s a turn to quality. More sustainable offices offering more amenities. Not just coffee and pizza, but mindfulness classes, good food, quality interiors: a really good experience.

Why do firms provide workers with what you call “super-experiences”?

Even before the pandemic, employees found it hard to come into the office and feel it was worth it. Most offices have been designed along two lines. One is optimisation of resources: sweating the assets, cramming people into space. The other is clarity. You go into the office and it's brightly lit and open-plan, so you can see what's going on. There's no ambiguity, curiosity or intrigue. Most offices are glass boxes with concrete floors.

If you went from optimisation of resources to empathy with the user, and from clarity into curiosity and offering things to stimulate the imagination, you would disrupt those two efficiency-driven axes. You would create something more imaginative. People would enjoy going to the office. Some firms try to do that. Since the pandemic we've had a lot of interest in super-experiences.

A super-experience may not be a large, spectacular, jaw-dropping design feature, but could be just a quiet nook, say, where people can relax. So experience, including experience-mapping and masterplanning, is part of the future of work.

Workspace designers used to be obsessed with process. They designed around the things people do, but forgot that how people feel about work is as important as what they do. You don't go into a restaurant just to eat. If that was the case, they would just have bare tables. You go for an experience of cuisine.

Now you go to the office for an experience of work. When workers have a choice where they will work, you've got to stop treating them as employees and start treating them as workplace service customers. So there’s a consumer service mentality coming in.

Companies provide workers with various perks to keep them in the office, but don’t the latter want a clearer boundary between private life and work?

There is a backlash against corporate intrusion into your life. But as soon as people take work devices home and allow themselves to be subjected to surveillance, a barrier has been breached. Hybrid working blurs the home-work boundaries.

People liked to go to work because you came out of the office, clocked off and work was over. Now we're always online. French companies are not allowed by law to contact their employees out of work hours. We'll see more of that.

There are drawbacks in dragging yourself into a glass box every day, but also in staying home. Not everybody has a dedicated workroom at home. People work on the kitchen table, while caring for children. It can get stressful. Many young people go to work because offices have more comfortable chairs and better wifi, so the boundaries between work and life are shifting. The pandemic shuffled the pack.

There's a generational thing too. I am in my late 60s, so I am more guarded about sharing my data. For younger people, their whole working life is a trade. They receive digital services in return for their data. They live a more open digital life.

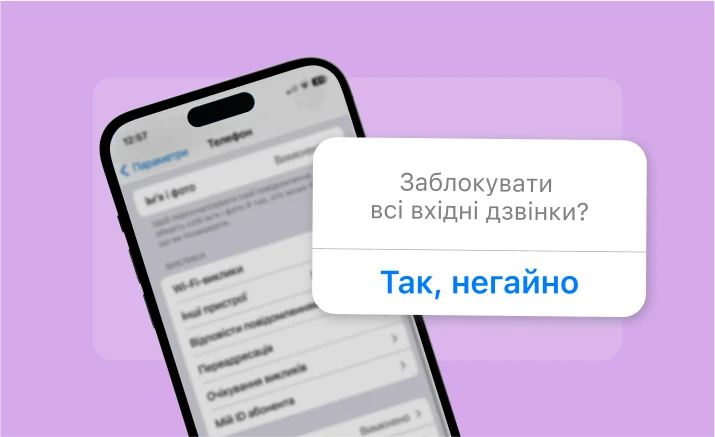

Think of the rise of workplace technology like digital wayfinding systems, room-booking, food-ordering and office attendance apps. There's a digital network around how we work. People use tech to make decisions about how and where they work.

The idea of Unworking is not that we don't work or work less, but that we rethink work. Work is no longer a place, which it was in the 20th century. It's no longer a process. It's more of an experience and series of choices. People get excited now. They have lots of choice, which is fine, as long as companies offer the right choices.

There's pressure on companies to come up with hybrid work policies. Our book’s message is that the modern office as we understood it since the 1920s is being reinvented, but not disappearing. As a node in a digital network, physical anchors will be stronger than ever, but smaller and flexible. Many offices will be repurposed as part of mixed use facilities, combining work, housing and leisure.

You argue that workers’ performance is now quantifiable. Doesn't that lead to digital Taylorism?

It does. We talk in the book about workers being monitored like athletes. When you have an appraisal, they don’t need to ask how you’re faring, since they have data on how you work. It’s an intrusion of privacy..

We trade data in every aspect of our lives. When companies recruit, they go on Facebook and find drunken photos of you. But employers can also use data to customise the environment to specific needs.. Based on data on a group’s characteristics, we can provide a certain environment, not one-size-fits-all solutions.

Do we need a virtual workplace and could the Metaverse be an early version of it?

The Metaverse is an early version of that. Suddenly in 2020 everyone was talking about Metaverse. Facebook became Meta and Microsoft was buying the world’s largest gaming company. Now the acquisition has stalled and the Metaverse balloon has burst, because people have problems putting on these clunky VR helmets.

The idea of achieving digital equality through people only meeting in a virtual place, is a draconian solution to a complex problem. How do you provide digital equality between remote and physical meeting participants?

It's hard to know which technologies will take off. Video-calling had been around for 20 years, but it only reached a point where it had mass adoption in a particular format.

Design is every bit as important as how technology is invented. User adoption is the key to commercial success, not technical ingenuity. We need both. Design is about the relationship between the user and the service. So design will be very important over the next few years.

Is there some sort of design that you see becoming the new mainstream, replacing open-plan offices?

Buildings are becoming smaller in the west. Asia Pacific is a different story. They give you real-time feedback, for example on who’s sitting at which desk. With new software and algorithms, designers have the opportunity to create floor plates that maximise sightlines for companies that want communication, natural light, proximity, comfort and good environmental conditions.

There's growing interest in co-designing, participatory design. In consumer electronics, community architecture, and neighbourhood planning they have been doing it for years.

We are moving from big open-plan offices to carved-up space. At Google’s new Mountain View campus, there are many hybrid meetings, so there's more enclosure. We're going backward, breaking out spaces into private rooms and cubicles. People may not own them, but book them through apps.

That's where design is going. More demountable, modular, reconfigurable spaces. Small rooms that you can fold back. Reconfigurable furniture and partitions are becoming more important.

Some firms encourage random encounters between employees to generate innovation, while others push workers to avoid any interruption. Is there a balance between the two?

It’s me-time versus we-time. That's where activity-based working comes in. Companies are introducing quiet zones, spaces where not even mobile phones are allowed. We will see more dedicated collaboration, concentration and contemplation zones where people relax.

The first breakout spaces were meant to help workers take a break. Then they added wifi, so people carried on working there. The game is constantly changing. Some organisations discourage social interaction and think the watercooler random encounter is overhyped. Others foster it.

However, there's good research on weak ties versus strong ties. During the pandemic, the strong ties people had with their closest colleagues got stronger, because they were the only people they were talking to, while weak ties got weaker.

The guy you meet on the train, the reception people, colleagues in the next department. Those weak ties are good for the organisation, but also people's personal well-being. If you talk to people on your way to work, you feel you're part of something bigger. There is a need to have weak and strong ties – and that’s another argument for the office.

What’s the role of the HR department in this new environment?

Traditionally in large companies, HR was in charge of people policies, IT of tech, and Facilities of office space. They operated in silos. Facilities were responsible for workplace experience. But you can be in a beautiful office where the wifi is not working properly; nowadays, if the IT falls over, you're in trouble.

We now see Chief Experience Officers and Chief Technology Officers being responsible for experience. HR deals with policy and framework, whether you can work from home, so they're in the front seat. HR is getting savvy to the experience angle and collaborating more closely with Facilities and IT on issues like what equipment should go home and what network remote workers should be using.

HR is leading the charge, providing a more integrated service. Employees have choices and make decisions. So HR, IT and Facilities have to work more closely. There's got to be organisational re-wiring to make the ‘people-place-technology’ approach more joined-up and aligned with organisational culture and mission.

Flexible working is not just a crisis of space, but a challenge to organisational structures.

Бажаєте отримувати дайджест статей?